Summary

What is it?

This is a 15 decade Paternoster, consisting of 150 coral beads strung on silk, with a carved bone finial above the silk tassel.

What was it used for and who used it?

Paternosters were a sign of both piety and ostentation, carried by people of all social classes from the 13th century onwards. They were ostensibly for the counting of prayers, but also served as a symbol of religion and an item of jewelry.

What time/location?

This particular paternoster is patterned after that shown in the Très Riches Heures, dated in 1410.

What materials and process were used in period?

Coral beads were an expensive but common choice amongst those who could afford them, and silk strings are mentioned in a number of inventories. The coral would have been carved by hand into beads, and strung on hand-spun silk thread or fingerlooped silk braids. The finial bead would also have been hand carved.

What is different from the period version in materials or process?

The coral beads used are probably dyed, and probably stablilized with plastic resin. They were sold to me as coral, but the price was such that that was probably a polite fiction. They were chosen for appearance and weight – another alternative such as glass or gemstone would be too heavy in a paternoster of this length and size.

The terminal bead is carved bone rather than carved ivory, for reasons of legality. All beads are purchased, as I do not have the skill for the carving of beads.

What would I do differently in a future version?

I need to do more research on the construction of tassels in the 14th century, and on my next paternoster I need to shorten the cord as much as possible – the beads are now looser on the string than they were when it was first strung because their weight has stretched the silk. However, this space between beads is not dissimilar to images of medieval paternosters.

Discussion

In both the April and May scenes of the Très Riches Heures of the Duc of Berry, the most prominent female figure is wearing a red paternoster. This paternoster is an attempt to copy the look of this paternoster as closely as possible with modern materials.

Paternosters were first noted in the 11th century, in a will of no other than the infamous Lady Godiva – she bequeathed to the monastery she founded in Coventry “the circle of precious stones she had had put on a thread in order that by touching each one as she began each of her prayers she might not lose count of their number” . They continued to be used by those in religious orders for the next two centuries, especially those without the literacy to recite the full complement of 150 psalms. This practice spread to the lay brethren and thence to the rest of society, from older women in the 13th century to all walks of life by the end of the 14th century .

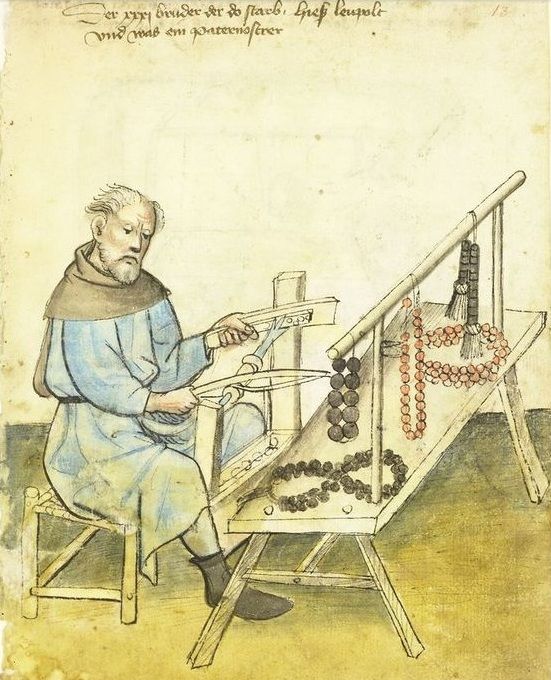

In Paris, paternoster makers were formally regulated into three guilds by as early as the 13th century – the guilds consisted of those that worked in bone and horn, those that worked in coral and shell, and those that worked in amber and jet. No mention was made in these regulations of the strings these beads were strung upon, though there are images of the bead makers at their trade.

Given that there was a guild devoted to their manufacture, it can be assumed that coral was a popular material for paternosters. Perhaps one popular reason for this was a belief in its curative powers. As Albertus Magnus’s manuscript on the virtues of herbs and other items, Le Grand Albert des secretz des vertus des Herbes, Pierres et Bests. et sultre livre des Merveilles du Monde, d’aulcuns effetz causez daulcunes bests from 1515 had this to say in Liv. ii, fol. 9 recto: “”To still tempests and traverse broad rivers in safety was the privilege of one who bore either red or white coral with him. That this also stanched the flow of blood from a wound, cured madness, and gave wisdom, was said to have been experimentally proved.”

Coral was sourced from fishers off the coasts of Catalonia, Corsica, Sardinia, and Barbary, where the finest coral was sourced. These coral beads were highly valuable – as much as 48 livres per pound, at a time when a master craftsman polishing those same beads might make only .75 livres per day .

Coral was very fashionable in the early 15th century – coral paternosters appear in any number of noble inventories and wills, and Margeurite, Duchess of Burgundy in 1405, owned over 70 coral paternosters. Several of these are noted as being worn as baldrics , “so as to make a scarf” . So it is a reasonable assumption that the dramatic baldric shown in the Très Riches Heures is also of coral.

Paternosters of this type were often finished with tassels, or with pearled buttons. The paternoster pictured in the Heures appears to have both, perhaps similar to what is shown in the Hours of Catherine of Cleves . The bead chosen to end this particular paternoster is similar in appearance to these bead-and-tassel combos.

Silk was typically used to string paternosters . This could take the form of stranded silk or silk braids – other materials used included gold and silver thread, but as paternosters often had to be restrung, inventories say less about their strings than about their beads . This tendency for them to break leads to many extant paternosters having somewhat random numbers of beads, like 63 or 103 . However, they usually started their life as a number of decades of beads – usually multiples of 10, sometimes of 8 – with or without marker beads or “gaudes” .

Construction of this Paternoster:

- Based on several mentions of 150 bead paternosters, I decided that was the appropriate number of beads for this paternoster. After measuring the apparent final length, based on the images, I decided that 12-14mm beads would be the appropriate size and after rather extensive searching for beads which met my budgetary requirements, found the beads in question. I’m not entirely sure they’re 100% coral, and I’m sure they have been dyed. However, they do meet one requirement of a paternoster of this size, which is that they are a similar weight to real coral – I have another rosary of only 80 bedes, of approximately 8mm in size, but of agate, and it weighs more than this one. A rosary of this length in a glass or semi-precious stone would never stay on one’s shoulder, even when pinned.

- The finial bead was purchased as well, after determining that something in a 30mm or larger size would be appropriate to match the art.

- The beads were strung on 2 stands of Trebizond silk, a strong filament silk that I thought would hold their weight. The color was chosen to match the illumination’s tassel. A braided cord would have been more resistant to abrasion, but I had a limited amount of thread to construct both tassel and cord. In addition, the beads were narrowly drilled and I was concerned that a braid would not fit through the holes.

- After wearing this rosary for ~30 hours, the silk has definitely stretched with the weight of the beads. While this is slightly concerning, it does allow sliding the beads as one “tells the bedes”.

- The tassel was constructed of the same silk as the beads were strung upon.